This article is based on oral interviews conducted with Terry in 1993 & 1996. They have been transcribed exactly as told.

Born in Sydney

on May 4, 1920, Terence John

("Terry") Dowling was the eldest child & only son of Herbert John

& Margaret.

Within a few years of his birth, his parents moved to the small far south coast township of Pambula where his father had been born & raised and where the Dowling family

had lived since the 1850s. Terry's great grandfather William had been the

original selector of the South Pambula property he named Punt Hole Farm. The holding is known today as Boondella. Terry noted "That

was selected bloody land, old Billy Dowling selected that, old Bill & his

gang...well that was a hundred & twenty bloody years ago..." Named

after Punt Hole, the spot in the river from which local produce was transported

down stream to waiting ships, Terry pointed out "It's hard to believe that

a fair sized boat come in to that Punt Hole isn't it, so it gives you an idea

of how the Pambula River has sanded up..."

|

| John Dowling at Punt Hole Farm. |

His two younger sisters were born in Nurse Cousemacher's lying in hospital in Bullara Street, Pambula. However, after his father passed away in 1929, his mother, herself a Sydney girl, made the decision to return to the city, taking Terry & his siblings with her. This was during the harsh days of the Great Depression, when the razor gangs reigned supreme & not surprisingly, it didn't take long for the curious country kid to become acquainted with their activities on the inner city streets. Terry remembered one in particular, "Chow" Hayes, commenting "...there was a gangster years ago by the name of Chow Hayes, this was when the razor gangs were in, Tilly Devine & all, this Chow Hayes , I thought he was bloody dead years ago, there was this newspaper article, it must have been in the Age, & here's this bloody photo of Chow, this is only last year [1995], now he'd have to be in his nineties, it was about another gangster, & he shot him, put four or five bullets in him, & he said 'If I thought the bastard was still alive, I'd have put another one in him', I don't know how many years he spent in prison, but he'd just got out, I remember Chow and those razor gangs, I'd be one of the few still around that would know them, well I was only a kid that they never worried about..."

Terry always maintained that during those harsh,

impoverished days, even the rats were dying of starvation in the city, so the

young lad decided to head back to Pambula. He pointed out that "...the

widow's pension that my mother got was her rent for me, right, so I came back &

lived with my Grandmother & then my Aunty. Well that enabled my mother &

two sisters to have a roof over their heads in 27 Little Cleveland Street,

Redfern..." an address that he recited with disdainful emphasis right up

until his last days.

|

Terry's aunt Deletha, with whom he lived after coming back

to Pambula.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George. |

With money in short supply, he took a train as far as the

few bob he had in his pocket would take him, & then took to "shank's

pony". "I got a train back as far as whatever bit of money I had, &

then as soon as I seen bloody daylight, I was walking, & a vegetable bloke

picked me up somewhere along the road, the old bloke gave me a bloody good

lift..."

Back in Pambula, Terry led the carefree life of a country

kid. He lived first with his Grandmother in the little weatherboard cottage next

to the School of Arts (now the town hall), & then later with his Aunty, Uncle & three cousins,

Ernie, Mick & Allan ("Bubby") George, in the house that stood in Merimbola Street where the Oasis Units are now located.

Although they was never had much as far as money was concerned, Terry always insisted that life was much better in the country compared to the city during those Depression years. "When I came back to my Auntie's place, we lived like Lords food wise. We always had a good garden, chooks, plenty of butter, fresh milk, cream, we had a bloody old fishing net...& we'd go down & set that behind the race course & get half a corn bag or a corn bag of beautiful fresh fish, all sorts, Christ we lived well. We never had any money, but listen, nobody else had any money either, everybody was used to that, but as far as food, & we had a good bed to get into, we had plenty of bloody blankets." It was during these Depression days that Terry's philosophy on life was born - he maintained that as long as he had a roof over his head, a dry bed & food in his belly, he had everything he needed in life.

Although they was never had much as far as money was concerned, Terry always insisted that life was much better in the country compared to the city during those Depression years. "When I came back to my Auntie's place, we lived like Lords food wise. We always had a good garden, chooks, plenty of butter, fresh milk, cream, we had a bloody old fishing net...& we'd go down & set that behind the race course & get half a corn bag or a corn bag of beautiful fresh fish, all sorts, Christ we lived well. We never had any money, but listen, nobody else had any money either, everybody was used to that, but as far as food, & we had a good bed to get into, we had plenty of bloody blankets." It was during these Depression days that Terry's philosophy on life was born - he maintained that as long as he had a roof over his head, a dry bed & food in his belly, he had everything he needed in life.

|

Deletha "Stump" George, Terry's aunt.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George. |

Despite, or perhaps because of, those harsh economic times,

the local community looked after its own, & Terry remembered the

cooperative small town spirit & helping hand constantly extended to family,

friends & neighbours with fondness. "You didn't swap anything, you

gave somebody something which you had excess to...I went with my Uncle one

night & he caught a bloody Jew fish...about five foot long...no

refrigeration, just the old Coolgardie...the next morning he was butchering

that up to take across to Mrs. Radford, well he probably had fifteen or twenty

bloody pound of big cutlets...if you knew somebody with a big mob of kids &

you just had excess things, well then somewhere along the line, those poor

buggers, they'd do something for you, if they never had any money, they'd do

something, do their best anyhow."

Even the "swaggies" that were constantly moving

through the region would get & give equally. "They never come &

asked for bloody nothing, they'd ask you if they could do a bit of work for

food...Well everybody had a wood heap right, & mainly they'd have these

bloody old knotty logs, & these poor buggers, they could split it, but even

young people back then, they seemed to be more experienced...There'd be twenty

mainly young people walking from Sydney to Melbourne & vice versa, they'd

be crossing each other, camping in the bloody old tennis courts down there, the

football ground, well the next day the coppers would be down there to move them

on, too right, never let them stop too long in the one place."

Pocket money was unheard of, but Terry & his mates were

always on the lookout for a chance to "...make a buck..." With local

blacksmiths Bill & Dan Smith offering 1/6 a bag for charcoal, Terry &

Bubby saw an opportunity too good to pass up. After spending £3/10/- on an old

eighteen-foot clinker built boat, complete with anchor, ropes & two or

three tins of paint, the pair cast an entrepreneurial eye over timber growing

on the town common. They promptly set fire to the area & burnt everything

in sight, & then spent an industrious day bagging the charcoal up for sale.

Loading their precious cargo into the boat until there was barely any

freeboard, the teens set off up the river, propelled by an old bamboo blind

hoisted on an oar. Everything was going well...until a gust of wind drove their

boat up onto oyster leases, ripping the bottom out of it & dumping the

fruits of their hard earned labour into the water. Then, to add insult to

injury, the pair had to walk empty handed all the way home, where they promptly

"...got into strife..." for being late for milking!

Dan & Bill Smith were the focus of another of Terry's

tales, this one centring on a practical joke gone horribly awry. "There

was an old bloke, Jockey Gleeson, who lived opposite Auntie's place, where

Ronnie Haigh lives. Old Dan & Bill had the blacksmith's shop that Kevin

Fanning's father had...they had a bit of a mine somewhere...mainly those times

they'd be blacksmithing up tools & that sort of thing, & this old

Gleeson comes in this Saturday to pick up his gear at the blacksmith's shop.

Now Bill & Dan had quartz that they broke, melted brass on the forge,

tipped it into the bottom of the quartz & pressed the other quartz into it.

Well now, if you've ever seen anything like gold in quartz, that was it, they

were having a bit of a joke with old Jockey see. They had an old sugar bag

planted, & this old blacksmith's shop was a bit dark, no bloody electric

light or nothing, & of course they take him in & show him this gold.

This sent old Jockey off...he went down & shouted for everyone in the pub,

right. He said 'Dan & Bill's cracked it!' & they said, 'What are you

talking about?', & he said 'They've found this reef.'...Poor old bastard,

he probably spent all the money he had buying grog & celebrating old Dan &

Bill Smith's bloody success...By Jesus, that turned out sour in the finish with

poor old Jockey, their friendship & everything busted over it...What

started off to be a practical joke, see, it busted the friendship & nearly

sent old Jockey bloody silly, that's how it affected him. Of course the gold

had affected him in the first place, anyhow, he went out & camped in the

bush...he was married, I don't know whether his wife left him, pissed off or

what, but the gold got him that bad, he went bush, he was that mad on gold that

he went & lived with it...Poor old Bill & Dan, they were bloody upset

too, because they didn't mean it, they were always playing jokes on one another

see, & this time it backfired, he never spoke to them again..."

Terry's school days were spent at Pambula when students

numbers stood at around seventy, with just Mrs. Woollard & Principal Mr.

Haines teaching two classes. Empire Day & the Queen's Birthday were

important annual events, & gardening was a subject he took to with gusto.

"We'd do weekly gardening lessons, my bloody oath we did. Our old headmaster

was a pretty cluey guy, wish I'd listened to him a bit more, my bloody oath, he

was no fool, old William Gorrie Haines...But you were all junior farmers

because every bloody junior had to milk a cow before he went to school...you'd

get home & milk the cows, well you had no milking machines so you had to do

it..." It was during his school days with Mr. Haines that Terry developed

what would become a life-long love of gardening, something that remained with

him for the rest of his days, & even after moving to Morwell (Vic.), his

backyard was dominated by his treasured veggie patch.

|

| Pambula Public School, upper division, 1935.William Gorrie Haines is pictured fourth from left in the second back row. |

Public transport was unheard of in rural areas then, so

school children had to either walk or ride to school. Terry remembered "A

lot of poor bloody kids had to ride horses three or four miles & now

they've got buses picking them up. There was a paddock at the school for the

horses, but no bloody chaff or oats though, no nose bags for the poor bastards,

only the palings to eat, right."

Principal Haines was someone that Terry spoke about with

almost a touch of awe & reverence later in life. "I can remember the

first surfboard I ever saw in my bloody life, old Billy Haines, our old school

master made that out of balsa wood. You know all these modern surfboards

they've got now, old Billy Haines sixty years ago made them, my bloody oath he

did, bloody unsinkable they were. We never had the money to buy the balsa wood,

the glue or anything, Mr. Haines did it for us. We were supposed to be surf

men, we were the big surfers, all we had to surf on was a big chunk of

pine...but old William Gorrie said 'I'll make you something better than

that.'"

|

| A young Terry Dowling. |

"As far as the Pambula Surf Club went, we never had

enough money to go to friggin' Merimbula, so how could we compete against

anyone, like go up the line to Sydney, Port Kembla & where they were having

the big surf tournaments, we never had the money to go there, our parents never

had it, so there might have been some champions there, but the poor buggers

never got a chance."

The epitome of the Australian larrikin, many weekends would

find Terry cutting firewood for local Police Constable Bottrell as punishment

for some misdemeanour or another. He said that although he initially left

school at the minimum leaving age of fourteen, he struggled to find a full time

job, so quickly found himself back in the classroom at the insistence of the

policeman. "I couldn't find a job so bloody Bottrell sent me back to

school, see I was getting into trouble & he got sick of it. I cut the

bastard cords & cords of wood, & he said 'The best place for you is

back to school.'" Restocking his wood heap was the Constable's penalty of

choice for the young trouble makers around town, & Terry laughs at the

memory: "Old Puddin' Burgess & I cut some wood. Wasn't too sharp a saw

either, bloody old cross cut saw, we had to pull our bloody guts out with it...He

was alright though, old Bottrell, he was only trying to look after us, poor

bastard, jeez he had it, but he was alright..."

|

Harry Rule, Deletha George, Terry Dowling & George

Dowling at

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George.the Pambula River Mouth. |

Terry & his mates thought all their Christmases had come

at once when they discovered firearms & ammunition in a shed at the back of

the Pambula Voice office, but once again, Constable Bottrell beat them to the

punch. "There was these two brand new revolvers, '44's, with a big heap of

ammunition, they were in the back of the old Voice office, it must have been

when they were travelling with gold from the old Yowaka Mine. We were going to

pinch them, Puddin' Burgess & I...but oh Jesus, they'd blow a friggin' hole

in the friggin' ground, I'd hate to be shot with one. But they were brand new

mate, & boxes of ammunition, I don't know how they got in the back of

bloody Eustace Phillipp's shed...I've got a faint idea that Bottrell got them,

he didn't want them to get into the hands of us fellows right..."

Mention of the Constable reminded Terry of his first car, a Charon

ute that he purchased with money earned cutting & bagging wattle bark. "When

I was sixteen I bought this bloody ute for sixteen quid, which was one ton of

wattle bark, £16 a ton, that was what wattle bark was...Poor old Hocky Woods

who lived at South Pambula carted that ton of bloody wattle bark down to Eden

for me & he never charged me any cartage or anything, because he knew that

if he did...I wouldn't have enough to pay the old bloke, I can't think of his

name, but he was a carpenter, he lived in Eden, & he'd made this little ute

out of this Charon...well when I got the bloody car...it wasn't friggin'

registered & I had no friggin license, see Bottrell's up on the hill &

he could see me driving around the bloody lanes all over the place, so he was

giving me a bit of rev one day about something I shouldn't have done or did do,

anyhow, he said, 'What about this car you've got? You'd better come up &

get your license,' I don't know what I said then, 'I haven't got the money' or

I don't know, I just forget what I did say right, but he knew it wasn't bloody

registered & he knew I had no bloody license, but he let me get away with

it, see he wasn't a bad fellow, old Bottrell, he was alright, nothing wrong

with him..."

|

Terry dropping a line in.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George. |

"By Jesus, we had some fun with that car, it was only

seven horse power...no friggin' brakes, we drove it over to Brereton's, to

Ken's fishing, old Stump [Terry's Aunt] & I, we used to run it on kerosene,

we never had the money to buy bloody petrol, but by Christ she was buying a lot

of kerosene. You only had to unscrew the carburettor bowl & fill that up

with petrol & then she'd fart & blow & away she'd go...we'd go down

fishing at Brereton's there down at the mouth of the river in Summer time, &

when you leave Kenny's to go up that sharp little bit of a hill, well there was

only one way I could up there, I had to go backwards, it wouldn't friggin' well

pull up in first gear, it wasn't strong enough, you'd have bloody flames flying

out of her before she had any go in her, mate...it wouldn't pull a bloody sick

old mouse over, we'd be going up backwards & old Stump would be screaming

'Watch where you're going, where are you going?', & I'm saying 'I'm still

on the friggin' road woman,' & then at the top you'd swing towards that

little road down to Middle Beach, hard left, she'd go round screaming, full

lock you know, because you had to keep revving, but she'd be firing then until

she got to where the bowling club is [Lumen Christi], she'd be hot enough by

then. By Jesus, though, by the time you got into the friggin' old shed, she was

about to blow, old Stump would be out of it & running into the kitchen

screaming 'It'll catch on fire, it'll catch on fire,' & I'd be saying 'On

fire my arse woman!'"

|

Terry with his beloved Aunty Deletha, or "Stump"

&

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George.his son George at the Pambula River Mouth. |

Colour, creed or social standing meant very little to Terry

- he took people as he found them, & when asked about the small party of

Chinese market gardeners who lived in Pambula during his youth, he simply

commented "They were bloody good people." He remembered "They

were directly behind the bakehouse, the bank, the Dr.'s Wing, all in that area,

they went down into that little gully behind the Top Pub...there was a little

bridge across there, I think there's a big motel on the corner there now...they

were growing carrots, parsnips, spuds, rock melons, we used to be down there

trying to pinch them for something to do!"

"At one stage there, they had a pretty big

garden...They all lived in there together, one camp right in the middle of

it...They had a little timber house, iron roof, it was a respectable little

joint right in the middle of their garden...They were just ordinary guys...just

ordinary old working clothes the same as us, oh they had those old Coolie hats

in hot weather, but other than that, they were just ordinary old blokes."

.jpg) |

Terry (left) & Bubby fishing at the Pambula River Mouth.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George. |

Doing the rounds through the township with their vegetables,

Terry remembered "...they never had a bloody horse, all they had was this

little cart & a bloody strap, & one bloke would pull that around the

town, he'd have a little chock that he'd drop under it to hold the shaft up &

they'd go to a house & the woman would come out & get her few spuds or

carrots or parsnips or whatever...This old Lambie [one of the Chinamen], he'd

take his cart to the show & sell his stuff & then he'd get pissed...old

Lambie would get pissed at the Pambula Show, well he'd pay us blokes to take

him home, we'd put him in this friggin' cart & pull him home & he'd pay

us, I forget how much, but it was pretty bloody good money, three or four bob

each, we'd pull him home & then get him out of the bloody cart there."

This reminded Terry of another of his enterprises - catching

& delivering echidnas to the Chinese gardeners. "I tell you what, the

Chows used to love those bloody porcupines, those echidnas, I hate to say it,

one & six they'd give you for them. Puddin' Burgess & bloody Jackie

Newlyn & I walked that bush, we bagged every bloody poor old echidna up for

the friggin' Chows, wouldn't matter if you took them friggin' fifty, they had

the money to buy them, they must have loved them...we took them to them live,

they didn't want them any other way bar alive, not damaged or nothing, I don't

know how they cooked them, but it wouldn't matter if you had bloody fifty,

they'd pay for them, the poor old bloody porcis..."

|

Terry with his four sons & Michael George, the son of

his cousin Mick.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George. |

Although Terry remembered about four or five Chinese

gardeners in Pambula when he was young, they gradually disappeared over time.

"...one would come & go, I don't know where he'd go to, but he'd

disappear for a bit & then come back...they were pretty old blokes, they'd

be 70 or 80 years old see, pretty old guys, but all of a sudden they must have

left the place. I think it got down to two, & this old bloke, Lambie, he

was one of the last two there..."

Farming & agriculture were the dominant industries in

the district during Terry's youth, when around 130 individual farms dotted the

area down to Kiah, up to Towamba & around the Ten Mile, but he noted with

regret how far numbers had diminished over the years. "...the last time I

was at Pambula there was only one bloody farmer the Victorian side of Bega

supplying Bega with milk, Bennett's old farm, there wasn't a friggin' farm

left, it's full of friggin' donkeys & horse riding & this shit, right.

There was all big families see, they had a few cows, they had chooks, a few

cows, a bit of butter & cream & they sent a bit of cream to the butter

factory... All out round Six Mile & Greig's Flat & where Fourter's &

that lived, Nethercote, see, farms everywhere, not a lot of big farms, but

they'd have a bloody can or two of cream there, & there was a butter

factory exporting butter directly to England...what's it now? Friggin' donkeys!

Hasn't the place gone backwards?"

|

Terry's eldest son George with his catch.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George. |

Although a baker by trade, Terry turned his hand to many

occupations over the years - milking cows, helping on dairy factory cream

collection rounds, loading sleepers in Eden

& roof tiling, among other things, but his first job after leaving school

was trapping rabbits. "In the Winter time we were busy chasing rabbits,

money in the bunny, money in the bunny!", he recites.

"I'll tell you what, we usually used to throw the

carcase away & keep the skins. Now they throw the skin away & keep the

carcases...Funny how cycles turn around, that was when people had very little

to eat & rabbit trappers were catching thirty, forty, fifty, one hundred a

bloody night & they'd just throw them in a heap & let the crows eat

them, all they were after was the skins. Our rabbit skin export was second to

our bloody wool. Did you know that? That's bloody right mate. Our fur trade &

rabbits in the whole, what we exported to England

was second to our bloody wool clip, second biggest export. Export of coal,

beef, iron ore & everything right, that's how many rabbits were in

Australia...they used it for hats, underlay for linos & carpets, coats, all

sorts of bloody stuff...I can remember buyers coming around, but they bought

them with the skin on...see when I was going to school, you'd take the rabbits

into the bush & you'd throw them away, because everybody had rabbits in

their bloody front garden, they were everywhere...there was hardly a thing of

buying a rabbit because they were so plentiful, it didn't matter where you

went, there was no myxo, no calici & no disease amongst them, all they did

was kept multiplying & breeding & spreading from one end of Australia

to the other, there was nothing to curb them, none of this scientific

business..."

"If I set traps or went ferreting, Ernie & I, or

Bubby & I, we caught ten or twenty rabbits, I used to have to get the best

two out of the lot & they would be cleaned immaculately, & Aunty had a

lovely silver tray & a bloody white table cloth & I used to put these

two rabbits on the bloody tray & I'd take them up to old Mrs. Tommy

Robinson, knock at the door, come in, put them on the table, take the bloody

starched white tea towel off from over them & she'd poke & prod &

turn them over & look at these two rabbits & she'd only take one, six

pence, I had to take the other one straight home & Aunty would cook it ,

because they'd be two perfect rabbits but she wanted the choice of two, &

when she got the choice of two, six pence without blinking an eye."

.jpg) |

Terry with his sons as well as those of Ernie & Mick

George, two of the

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George.cousins he grew up with at Pambula. |

The simple things in life were definitely the best as far as

Terry was concerned, & never was he happier than when he could trap a few

rabbits, shoot a duck for dinner or hook a fish fresh from the ocean. These

were loves that he shared first with his four sons & then later his

grandchildren, but he was less than impressed when new laws were introduced

that put paid to those activities. "I'll tell you what though, I don't

know about NSW, but if you're caught in Victoria using a steel jaw trap, you're

fined twelve thousand bloody dollars, $12,000 if you're caught trapping a

bloody rabbit...see there you are, I've got a hundred rabbit traps, I can't do

a friggin' thing with them, nobody wants them, I can't set them, & I can't

sell them, I could probably give them to somebody, but then what can they do

with them? So what do they do, poison them! And then I've got a shot gun that's

forty bloody four or five years old, & I've got to hand it in.

Unbelievable! I say really it's unbelievable."

|

Terry & mate Harry Rule fishing near Jack Severs' Beach.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George. |

In terms of working, he pointed out "We were working

all the time, never got much money, but we worked. I remember turning the

bloody old sandstone over for Percy Radford when he was getting an axe ready

for a wood chop, you'd turn it over for half a day for two bob. Well then, in

turn, poor old Perc was a sleeper cutter, he only got two bob for cutting a

nine by bloody four by four sleeper, two bob, that's all those sleeper cutters

got for a hard wood sleeper, oh, that might have been black butt & other

stuff, I think Woolly butt & box might have been a bit dearer..."

Other sleeper cutters that Terry remembered by name were

Albie McCamish, Dick Miller, Chris Reedie, the Bobbins boys & Mick Perrin,

who he said "...was the king of the sleeper cutters, he used to cut about

twenty a day, other blokes would average about ten or twelve...see look, when I

was about ten or twelve, I used to go with old Goggie Haigh & bloody Les

Turner to all those sleeper cutters on the bloody trucks...that was a good

outing, going out into the bloody bush, way down over the border, all those

sleepers were brought back to Eden, so when you come to work it out, the

sleeper cutters had the bloody best of the timber cut around Eden to the border

supplying bloody hardwood sleepers to New Zealand & bloody India, so what

are the greenies yapping on about bloody wrecking the bush for? They got the

best of the friggin' timber there eighty years ago, seventy anyhow. Those poor

bastards...there wouldn't have been one in ten had a safe, they'd have a bloody

sugar bag with the bread & bloody bit of lousy meat...that's what they kept

their tucker in, & hung it in the shade..."

.jpg) |

Terry (third from right) with a few of his mates outside his

Morwell home.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George. |

It was just prior to WWII that Terry moved to Morwell in Victoria's

Gippsland region, & there enlisted in the 22nd Infantry Battalion of the

Australian Army in June 1941. As with many of that era, though, you were

wasting your breath asking him about any of his war time experiences - he'd

usually just brush over the question & promptly shift the conversation onto

another topic. However, his larrikin streak did show itself when he explained

why he opted to become a machine gunner "So I could shoot the bastard's

faster, before they could get me!"

Following the war, Terry married Morwell girl Queenie

Bolding in 1949, & they had four sons - George born in 1953, Dan in 1955,

Colin ("Spence") in 1956, & the youngest, John, in 1957. When

Queenie died suddenly in the early 1960s, Terry took to single parenthood,

continuing to raise his boys alone until joining forces with Peggy & her

children, between them raising the family that Terry referred to as "the

tribe". Despite settling in Victoria,

he & his family continued to visit Pambula whenever the opportunity offered

to catch up with his Aunty "Stump", Bubby, Ronnie Haigh & many

others & drop a line in the rivers & lakes.

|

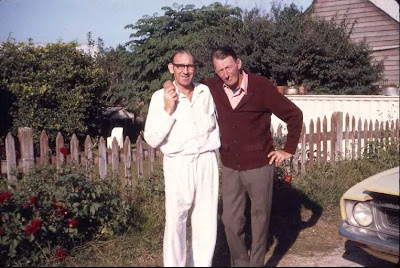

Terry (left) & Peggy (right) with Betty George in front

of Betty &

Bubby's Pambula home, C. 1976 on one of Terry's last visits before Bubby passed away.

© The estate of A. C.

("Bubby") George.

|

After a full &

busy life, Terry passed away on 2

September, 1998, doing exactly what he loved - out in the paddock

working. At his funeral, his family opted to forego the usual hymns &

prayers, instead farewelling him with John Williamson's "True Blue" &

"Old Man Emu", & what more fitting way to say goodbye to a fair

dinkum old Aussie bloke who epitomises what being true blue really means.

© Angela George.